People say American cities look alike, and I guess that’s true along their interstates and in their office parks, but the center cities are distinct. When I went for a run in Kansas City, Missouri this week, I kept stopping to look at the sights.

My route led past the “world’s largest shuttlecocks,” sculptures that are just what they sound like, and a neighborhood filled with Spanish-Moroccan architecture: red tile roofs and clock towers. I learned later that it was Country Club Plaza, one of the world’s first suburban shopping malls, completed in 1923.

The next morning a friend drove me through another part of the neighborhood called Westport. Some old commercial buildings seem run-down, but new apartments have gone up and it feels alive. We were near Union Station, the setting a few days earlier for the NFL draft, and we ate at the Filling Station, a hipster coffee shop.

The neighborhood got me thinking about how an urban landscape reflects the story, the narrative, of any given city. Westport is older than Kansas City itself, a former settlement of log cabins that was a starting point for the Oregon Trail in the 1840’s. The explorer John C. Frémont launched his expeditions there, as I learned while writing my 2020 book Imperfect Union. Kansas City later grew up around Westport as an edgy railroad boomtown that defied Prohibition, made a mark on jazz, and is now known for its Super Bowl teams. It has considerable diversity and long-running debates over race and inequality. A historic Supreme Court case in 1995 involved desegregating Kansas City schools.

I’d come there for a meeting about who tells the story of Kansas City and thousands of other unique places. NPR and KCUR convened a discussion about local news, which raised the question of who still covers it.

The answer seems more grim every year. The Kansas City Star, whose reporters once included Ernest Hemingway, is typical of metropolitan papers in that it’s laid off a lot of staff over the years. (A second local daily died decades ago.) Most advertising that made local papers profitable has moved to the Internet, and all but the most elite news organizations have struggled to make their digital operations pay.

The city still has local TV news, news websites, and two dozen or so people on the news staff of KCUR. But many places have fewer reporters than they did—and in some cases, nobody is left to tell their story at all.

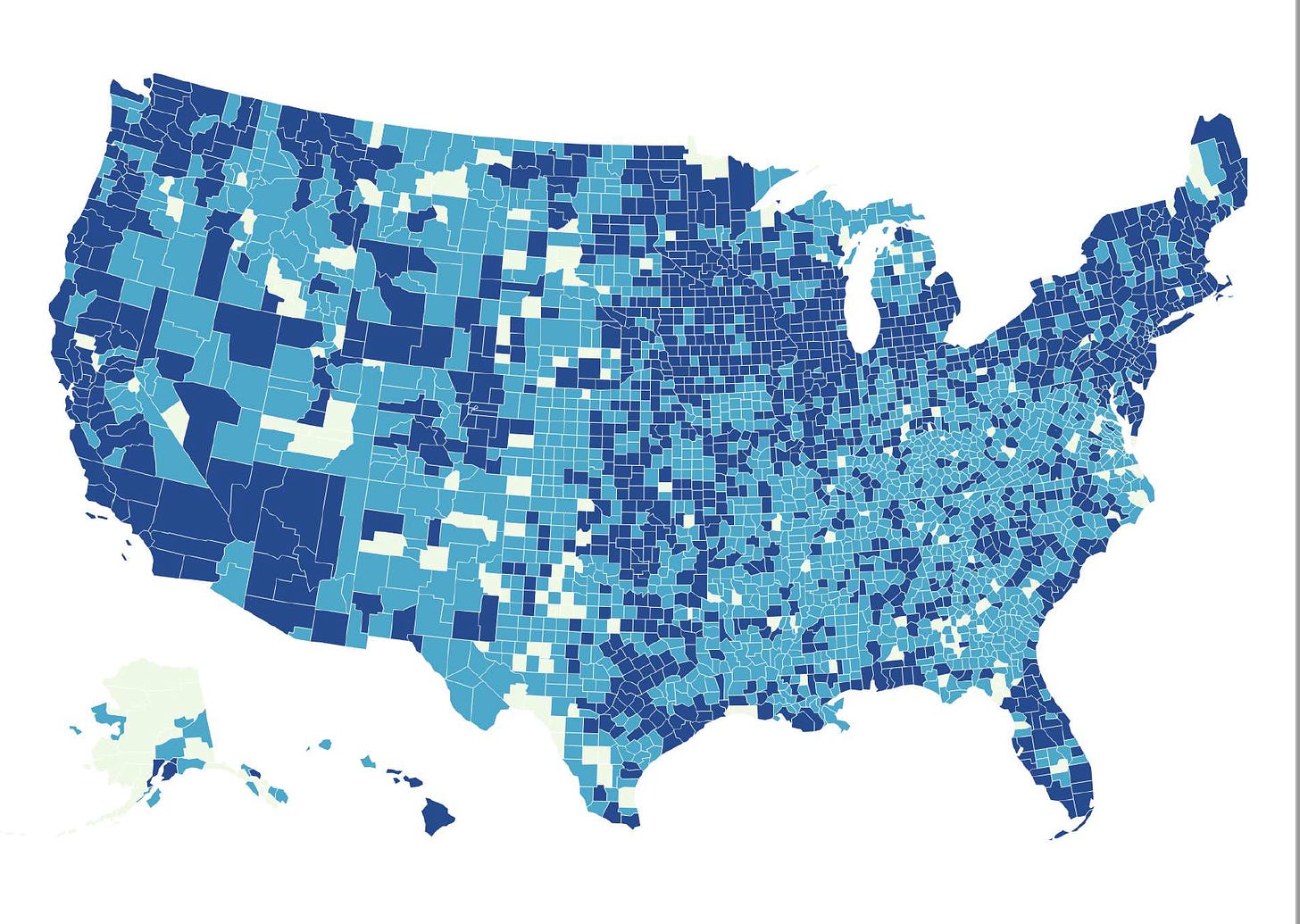

The people at the Kansas City meeting included Tim Franklin, a distinguished former newspaper editor who now runs the Medill journalism school at Northwestern University. Afterward we exchanged emails, and he let me share the above map of “local news deserts.”

Jackson County, which includes Kansas City, is dark blue, which means it has multiple news sources. But about half the counties in the whole country are light blue, which means they have just one news source. Some counties on the map are white, meaning they have no local news site within their borders. Some 70 million people live in counties with zero sources or just one.

Even where news sources exist, they may not do original reporting. “We estimate that thousands of local newspapers are effectively ‘ghost newspapers,’” Franklin said. “Basic beat coverage of local schools, government, courts and businesses is missing. That means residents in those communities aren’t getting news that can significantly affect their lives, like property tax increases, road closures, business failures and, of course, local elections.”

Franklin argues that local officials spend more tax money and act less wisely when they know a news outlet won’t hold them accountable. Political actors also have more freedom to make things up. Congressman George Santos famously fabricated his resume, but wasn’t vetted by the media until after his election. And Santos represents Long Island, which has more media than most places.

My brief visit to Kansas City did make me think that some things are better than in the past. Consider this scathing examination of the news coverage from an earlier era. In 2020, the Star looked into its archives and found that it had failed to cover the realities of local school segregation in real time. The paper produced a whole series on its past shortcomings on race. It would seem that the strong, stable local media of the twentieth century did some residents no good at all; people of color were living in a news desert of a different kind.

Today many newsrooms are more diverse, and there is more coverage, not less, of certain kinds of stories. The Star gives attention to perspectives it says it once ignored, and investigates policing. It’s been joined by new local news sites including the Kansas City Defender, which aims to serve a younger Black audience.

Its founder, Ryan Sorrell, told me the Defender is a “social media first” publication, meaning it often breaks its stories on Instagram. When I asked about his business model, Sorrell said he’s relying on small grants and donations, mainly from foundations that support local news. “We don’t practice the same journalistic norms” as an old-school paper, he says, and he certainly doesn’t have an old-school big staff. At 27, he’s the only full-time employee, with a few contributors. But the Defender has several times driven Kansas City news coverage—notably last year, when it pushed other media to pay attention to the disappearance of Black women.

It’s not the area’s only new publication. Residents point to the Kansas City Beacon, a nonprofit news site, which looks seriously at the nuts and bolts of local government. You can find operations like that across the country. In Texas, a nonprofit newsroom covers the state capital after old-time newspapers retreated. In several cities, newspapers have merged or joined forces with public radio stations.

My sense is that it’s not yet enough. It takes time and resources to cover a city well, and to get the story across to a busy populace. And I think a lot of us have lost the narrative of our communities. We feel this at election time, when we have extremely detailed opinions about presidential candidates but aren’t always sure how to weigh the candidates for city council.

We also feel it when we experience our country’s divisions. We share common interests with our neighbors, and might find ways to deal with them even when they are of the opposite party. But we don’t hear as much about them in a local context as we might. Local media aren’t there to connect us. It’s far easier to find and follow national news stories that divide us into Team Red and Team Blue.

It should be obvious by now that I haven’t kept the 400-word limit that I proposed for myself when starting Differ We Must. I’ll keep experimenting with different lengths.

I named this column after my forthcoming book Differ We Must, which tells Lincoln’s life story through his meetings with people who differed with him. To get anything done in his life, Lincoln had to deal with people he believed to be wrong.

That feels like a very modern challenge! So I aim to explore its modern dimensions here. While I hope you will preorder the book so you receive it on October 3, I hope you also will keep reading here. Sign up for a free or paid subscription if you have not. And join the discussion in the comments! I appreciate the feedback, even (or especially) if you differ with me.

One challenge to neighborhood newspapers in San Francisco (not a news desert, but the neighborhood papers often have news the Chronicle and Examiner don't cover), is that the Department of Public Works has gone all Marie Kondo, eliminating "unsightly" news kiosks on the streets.

I agree. Local newspapers are essential to cover the specific concerns of communities. I am proud of the Charleston SC Post and Courier www.postandcourier.com for its investigative journalism that has exposed corruption in our state. Just look at the Alex Murdaugh Murders!