I write this from a hotel restaurant in Atlanta, Georgia, the latest place where I’m discussing Differ We Must. The book—which seems to have sold a lot of copies in its first week and which is available at your bookstore or at this link—is all about the nineteenth century, but speaks to the present.

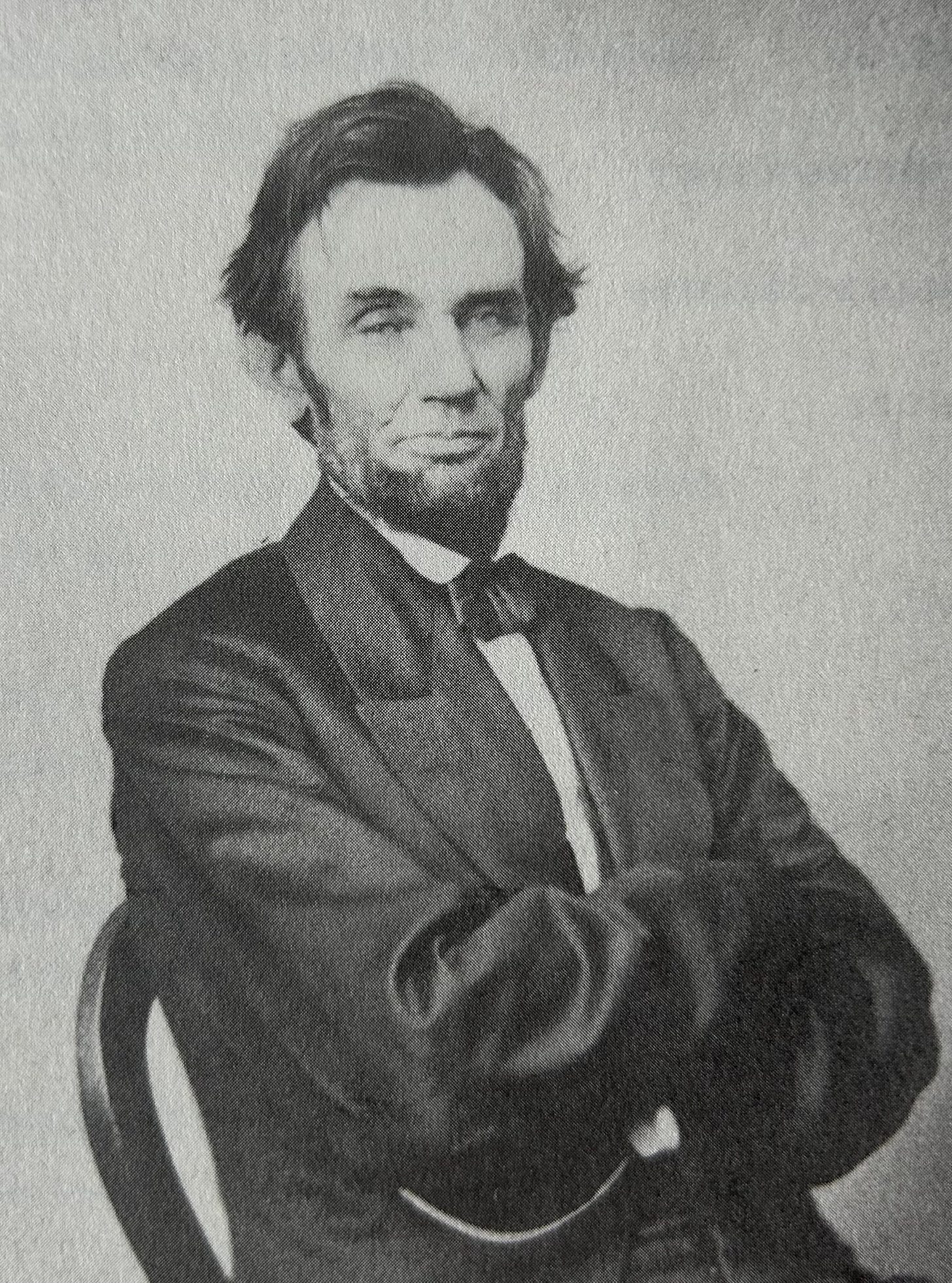

The city where I’ve just arrived illustrates the resonance. My duffel bag contains a copy of the book adorned with the face of Abraham Lincoln—the president whose troops burned Atlanta during the Civil War and whose Emancipation Proclamation decreed freedom for those enslaved here. Today Atlanta has risen as a very different and very prosperous city, filled with gleaming hotels and office towers and presided over by a Black mayor.

Washington, D.C., the city where I spoke last evening, is another place where the past resonates. Lincoln’s White House still stands, his office remade into the Lincoln Bedroom; a plaque shows the location of the desk where he served as a member of Congress at the U.S. Capitol.

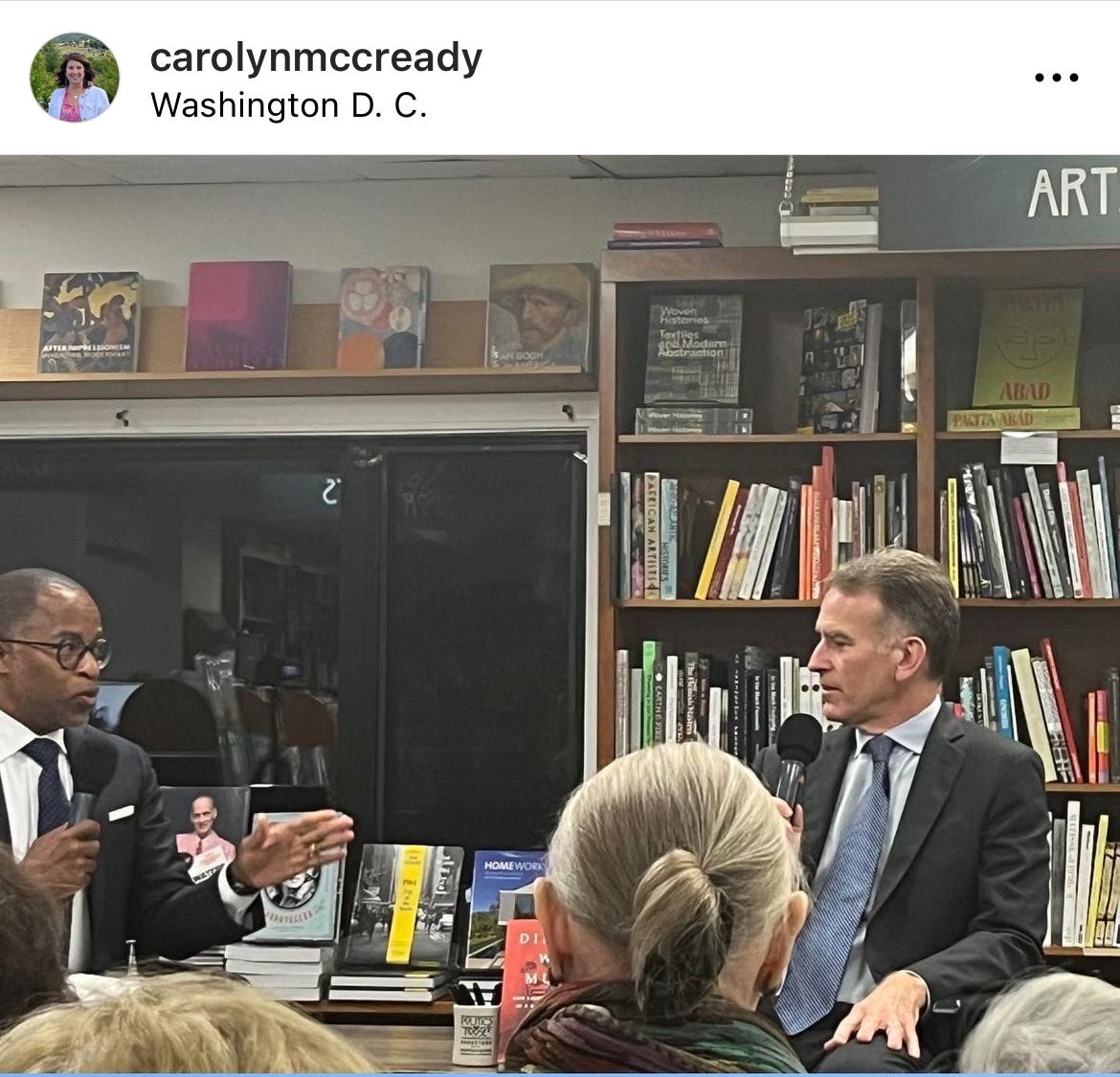

Washington’s Politics and Prose bookstore is filled with histories of this city and the country. There, I was interviewed by Jonathan Capehart, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, editor, analyst and anchor for the Washington Post, MSNBC, and the Newshour.

In his meticulous preparation for our encounter, Capehart had underlined passages throughout Differ We Must, and he took note of a major theme of it—what I call the “culture of equality.”

Differ We Must holds that Lincoln lived in and had to deal that culture. Americans were always likely to demand equal treatment and status—and were liable to drag down any man who acted like their better. We can recognize this culture today: when we say someone is “putting on airs” or “getting above himself” or “has forgotten where she came from,” we are calling out a violation of the culture of equality.

This complicated life for Lincoln, who wanted to rise in the world. It seems clear how he responded to it. Though he made no secret of his ambition, he also advertised his humble roots—saying the story of his youth reflected simply the “annals of the poor.” No matter how high he rose, he spoke with modesty, which grew out of political calculation as well as self-confidence. He didn’t need to puff himself up, and he knew it would hurt him if he did.

The culture of equality was tricky and vicious, liable to turn on those who used it. As a young political partisan in 1840, Lincoln wrote newspaper articles mocking President Martin Van Buren for spending thousands of dollars on White House drapes. It was a violation of the culture of equality, an insult to millions of ordinary men living in log cabins. Never mind that Van Buren was the son of a humble tavern-keeper, and Lincoln was campaigning to replace him with William Henry Harrison, a born aristocrat.

Then Lincoln married Mary Todd Lincoln, who came from a wealthy and powerful family—and immediately found himself targeted for seeking “aristocratic family distinction.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote his Democracy in America when Lincoln was a young man, traveled the country and observed this cultural trait. He said that in a democratic society, people’s “passion for equality is ardent, insatiable, eternal, and invincible. They want equality in freedom, and if they cannot have that, they still want equality in slavery.”

The reference to slavery is, maybe, Tocqueville’s unconscious hint at what was absent from the culture of equality as practiced in the 1800’s.

In our bookstore conversation, Jonathan Capehart called this out. The culture of the 1800’s didn’t seem too equal to him!

And there is no reason it should have. As the book notes, the practice of slavery was a monumental violation of the culture of equality, and hardly the only one. The principle of equality had spread widely among white men, but neither the law nor public opinion (among white men) extended it to others.

Update: the Penguin Press just authorized me to share an excerpt of the audio book on that gigantic exception to the culture. It includes the only incident in Lincoln’s luge in which he left a detailed recollection of an encounter with an enslaved person. Give a listen:

The story of Lincoln’s life—the story I try to tell—is of his effort to wrestle with this contradiction. Lincoln eventually picked up a theme from radical abolitionists, repeating a line from the Declaration of Independence “that all men are created equal,” and he made it a weapon against slavery. He called that phrase “my ancient faith.” His religious beliefs were never well understood, but his devotion to the Declaration was.

Today we still struggle with what equality means and who is entitled to how much of it. It is a political question (are people entitled to “equal opportunity” or “equal outcomes”? How do we define racial equality, or income inequality?). It also is a matter of culture.

Think for a moment of how our culture of equality is applied in everyday life. If a very rich man who was born into wealth can manage to talk a certain way and cast a certain image, he comes across as a man of the people. If another person applies their university education while working a modestly paid government job, they may be dismissed as an out-of-touch elite. We make intricate and ironic judgments about who does or does not violate the culture of equality. We’re on the lookout for someone “putting on airs” but sometimes more tolerant of a person who puts one over on us!

My study of Lincoln (and other nineteenth century figures) made me think much more deeply about our culture of equality, and about the world we experience today. If you choose to read it, I hope you’ll feel the same. Now if you’ll excuse me, it’s a little after two in the afternoon on October 11. I’m heading soon to an event at the Atlanta History Center, where we’ll discuss the past and the present some more.

It's probably no coincidence that FDR, one of the all-time greats like Lincoln, continued in that vein in his famous Four Freedoms speech.

“The basic things expected by our people of their political and economic systems are simple. They are:

Equality of opportunity for youth and for others.

Jobs for those who can work.

Security for those who need it.

The ending of special privilege for the few.

The preservation of civil liberties for all.”

And still the struggle goes on...

The fascinating story behind how that speech came together: https://www.timelesstimely.com/p/leadership-lessons-from-the-four