Brian Mackey—host of an Illinois Public Media show in Lincoln’s home city of Springfield, Illinois—asked me about Duff Green last week. Green is one of the extraordinary characters in Differ We Must—a newspaperman and propagandist who was known to presidents from Andrew Jackson in the 1820’s to Lincoln in the 1860’s.

In his earlier years, Green was an advocate for democracy and equality, at least among white men. He also had the courage of his convictions. Once his newspaper so insulted a member of Congress that the lawmaker beat Green and broke several bones. From his hospital bed he dictated an editorial repeating the insults. This made him a hero of the freedom of the press, even to people who loathed his words.

But the image of a public figure depends in part on which issues are most prominent in his day. (Think of the difference between Charles Lindbergh the heroic pilot of 1927, and Charles Lindbergh the America First isolationist of 1941.) Green lived long enough for the issue set to change. Slavery became the overriding national concern, and brought forth Green’s obsession with it. Though he defended his own independence to the point of being self-destructive, he believed in denying freedom to the enslaved.

In late 1860, after the election of his antislavery friend Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, Green met with Lincoln in Springfield Illinois. Green wanted the president-elect to support a “compromise” to avoid civil war. All Lincoln had to do to stop Southern states from leaving the Union was to support enshrining slavery in the Constitution.

Their unsettling encounter is one of the face-to-face meetings that make up Differ We Must—sixteen encounters Lincoln had with people who differed with him. This particular meeting is relevant to current events: former president Trump, while campaigning for a second term, told an audience that he could have negotiated away the Civil War.

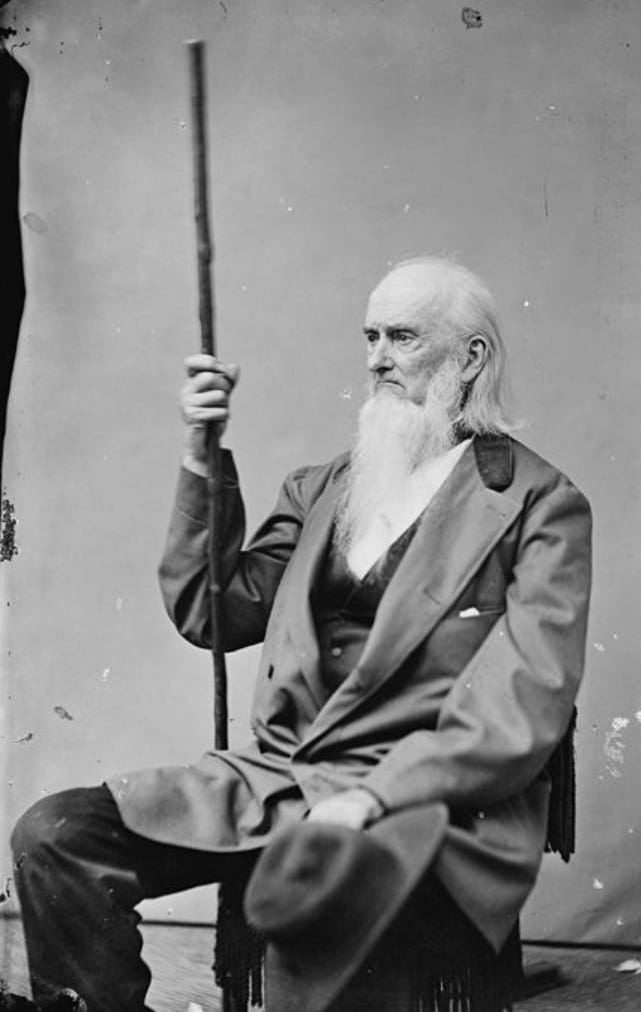

Duff Green.

The debate over slavery also feels relevant to our modern battles between labor and management, workers and capital. Differ We Must includes a statement by John C. Calhoun, the great tribune of slavery, who claimed in the 1830’s that slavery was a more honest and straightforward way of ripping off the poor than modern capitalism! Lincoln, in 1860, endorsed the right to strike as a part of free labor. While our debates are very different today, the resonances are useful, forcing us to clarify our own beliefs and assumptions.

The chapter on Duff Green includes the following description of an increasingly divided America.

###

On a deeper level the dispute wasn’t subject to compromise. Parallel revolutions in public opinion made that impossible. The North’s slow revolution had crystallized public hostility to slavery, while the South’s slow revolution exalted it. Slaveholders once had admitted the practice contradicted the country’s principles, that it was a tragic inheritance, a corrupting force, which Jefferson himself said must end. They blamed the British of colonial times for introducing it; but as it grew more lucrative, and also came under threat from the North, many practitioners stopped apologizing.

One scholar [Drew Gilpin Faust] concludes that from the 1830’s onward, slavery “took on the characteristics of a formal ideology with its resulting social movement.” In the 1850’s the Virginia intellectual George Fitzhugh said slavery had been the norm throughout history, and urged wealthy Southerners to vacation near home to avoid being contaminated by fashionable ideas against it: “Southern thought must justify the slavery principle, justify slavery as natural, normal, and necessitous.”

He didn’t think racism was a firm enough foundation; Southerners must proclaim that even white slavery was desirable. In his book subtitled The Failure of Free Society, Fitzhugh said free labor turned white workers into “pauper banditti” while making a few capitalists rich. The poor would be better off in a paternal system that firmly directed them. “Make the laboring man the slave of one man, instead of the slave of society, and he would be far better off. . . . Free society is a monstrous abortion, and Slavery the healthy, beautiful and natural being which they are trying to adopt.”

Lincoln knew of Fitzhugh’s notions; when he roared in his Lost Speech of 1856 that Southern newspapers were promoting white slavery, he doubtless was thinking of articles in major papers, like the Charleston Mercury, that were celebrating Fitzhugh’s book.

This was the gap that Duff Green wanted Lincoln to bridge, and he came as near as anyone to persuading Lincoln to try. Lincoln’s interest, if narrowly defined, might have called for him to seek compromise, drawing out discussion and deterring some states from seceding. But he wouldn’t do it. His moral sense would not allow it. His position was already a compromise, which had evolved out of political necessity and his understanding of the Constitution. He could give no more to the South without embracing their idea of the world.

As the New Year arrived he prepared to travel to Washington with the crisis still unresolved. Green soon made a journey of his own. When he next wrote a letter to Lincoln three years later, he was living in Richmond, the capital city of the rebellion.

###

Thanks for reading Differ We Must, a companion to my book of the same name. The book has triggered a lot of debate! And it reveals many stories that were new to me—like that of Duff Green—as well as stories that are more famous—like Lincoln’s meetings with Frederick Douglass and Jessie Benton Frémont.

My friend Anand Giridaharadas says he felt the book was a tonic, an escape from the news into a different time, even as it offers lessons for the present.

If you have already ordered it, thank you. If not, you can find it at the links below.

Differ We Must at Bookshop, an independent booksellers’ site

Fascinating read. Thanks!